Longevity, body size, and the joys of playing with data

04 March 2016

Tweet

I co-teach an MSc course in which the students are challenged to write a review paper on some topic in evolutionary biology. We (ambitiously) point them towards Trends in Ecology and Evolution as the kind of thing they should be aiming for. The best part of this for me is discussing topics with students. This often takes me to new places in the literature, makes me think hard about unfamiliar topics, and sometimes gives me opportunities to play with new data. This happened today, when a student expressed interest in understanding the links between body size and longevity in dogs.

Some background. Across most animals (vertebrates at least, I’m not so sure about the others), bigger animals live longer. Think elephants vs. mice. It seems kinda obvious. But the curious thing is that among breeds of dog, smaller animals live longer. I do a lot of comparative biology, and it’s always interesting to find trends that go in completely opposite directions. The challenge is then to answer three types of question: the proximate question (what current mechanisms, e.g. in development or physiology, cause these patterns?); the ultimate question (why did it end up this way over evolutionary time?); and the lineage explanation (can we propose a plausible set of steps that get us from a single ancestral mammal to the patterns we have today). Those are fun and enormously challenging things for the students to grapple with. But as a supervisor, I want to educate myself on the patterns themselves. I have my own questions. Are the patterns real? Are they convincing enough to care about? Do we have data to show it? Can we use the data to inform our answers to the important questions?

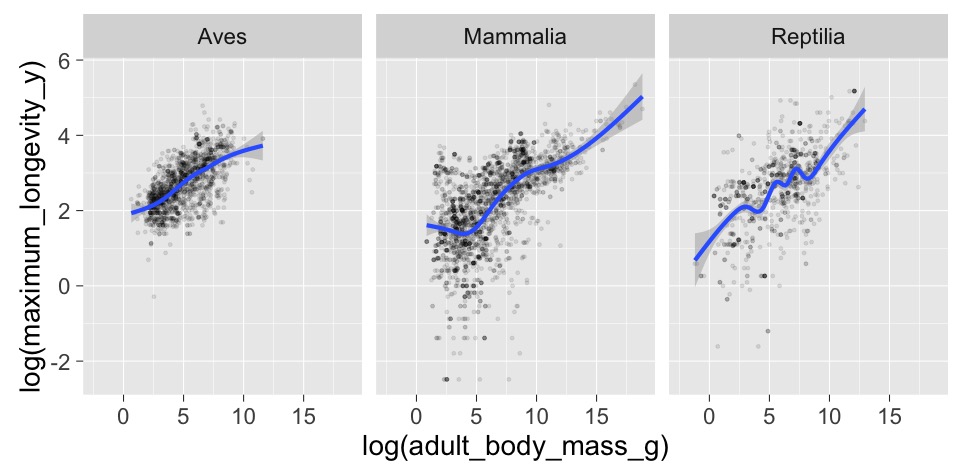

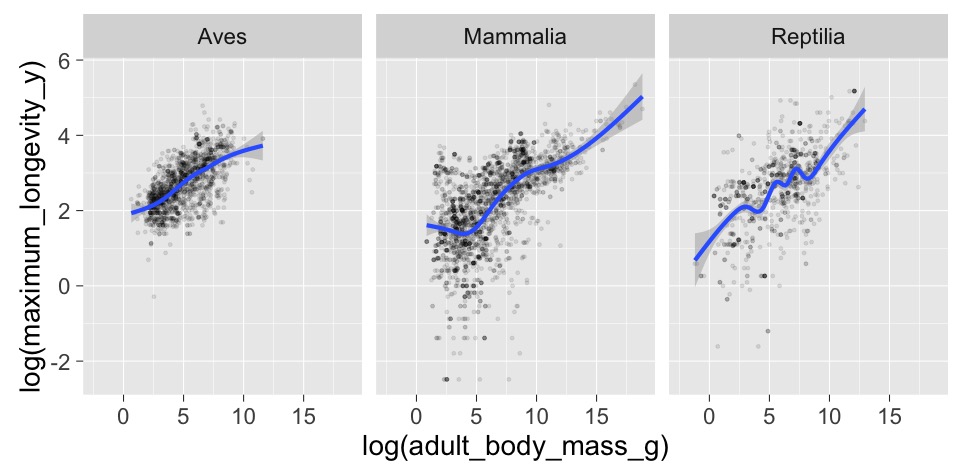

Playing with data is really fun. People are increasingly making their data available, and I hoped I’d be able to find suitable datasets to examine the student’s question, or at least demonstrate that the two conflicting trends are convincing enough that we should spend a long time thinking about explanations. For the between species data I turned to this paper [1, link fixed thanks to Ethan White], which describes a beautifully put together dataset on amniote life history traits, and which I happen to know about from hanging out on Twitter. Less than a minute after downloading the data, and with exactly 5 lines of R code, I can see for myself that bigger animals really do live longer, and that this holds true in birds, mammals, and reptiles. This is exciting! I’m not breaking any new ground here (there are umpteen papers on this and related patterns), but it’s fantastic to see the patterns for yourself, and explore them in whatever way you like almost as quickly as you can think of the questions.

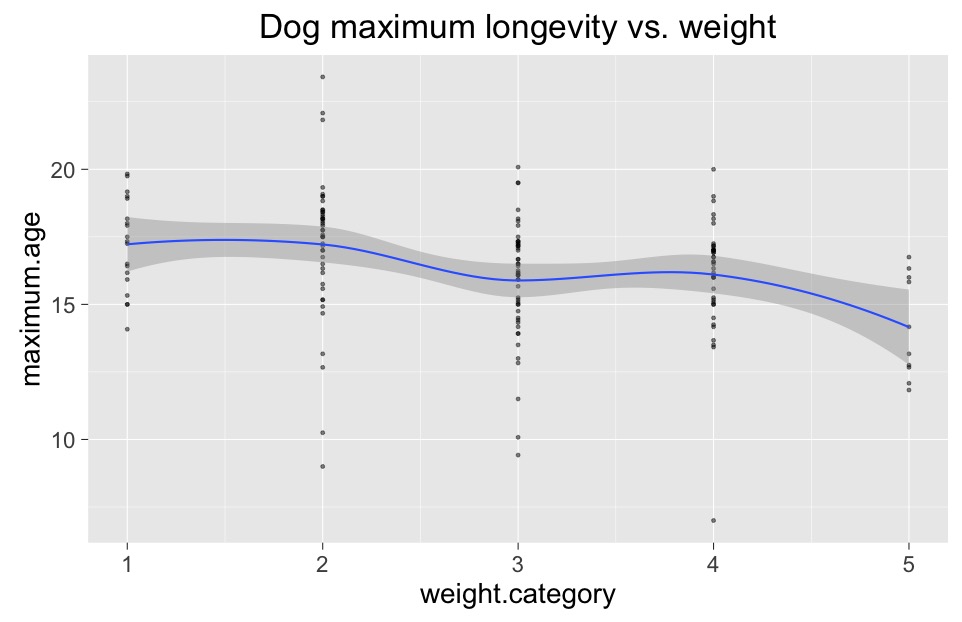

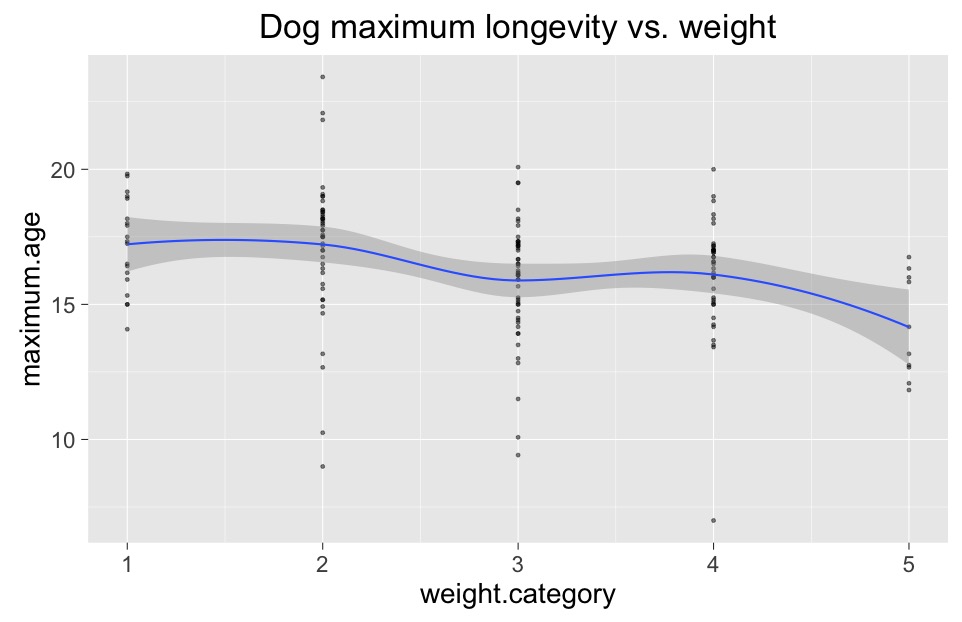

I thought getting data on dog breeds would be more challenging, and to a certain extent it was. But I was lucky with my google-fu, and quickly found this paper [2], which contains a nicely-formatted table on longevity in 165 dog breeds. It took me about 5 minutes to cut and paste it into a google spreadsheet, clean up the formatting for what I wanted, and write the 4 lines of R code necessary to see the pattern in dogs:

The data here aren’t quite as convenient - dog weight is given in categories rather than point estimates. But it’s good enough to convince me that something interesting is going on here: unlike the between-species patterns, bigger dogs live shorter lives than smaller dogs. That’s kinda odd. And now I’m left wondering why, and what other data I can find that might help inform our thinking here. Is the same true of other domesticated mammals like sheep, horses, cows, etc.? Is it true of subspecies or isolated populations of wild mammals? What about humans?

Science is often difficult, slow, and tedious. But sometimes it’s easy, fast, and just great fun. Exploring data like this is one of my favourite things to do, and one of the biggest revolutions going on in science at the moment is the huge increase in the number of well-formatted and well-curated datasets that are made public for all to see and use as they wish. We’ve still got a long way to go on that front (shameless plug) [3], but things are moving fast, and it’s a great time to be doing science.

My commute home will be filled with papers on the causes and correlates of longevity in mammals. That will be rich brain-fodder for the weekend. I wonder what my 3 year old will think.

[1] Nathan P. Myhrvold, Elita Baldridge, Benjamin Chan, Dhileep Sivam, Daniel L. Freeman, and S. K. Morgan Ernest. 2015. An amniote life-history database to perform comparative analyses with birds, mammals, and reptiles. Ecology 96:3109.

[2] Adams, V. J., Evans, K. M., Sampson, J. and Wood, J. L. N. (2010), Methods and mortality results of a health survey of purebred dogs in the UK. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 51: 512–524.

[3] Roche DG, Kruuk LEB, Lanfear R, Binning SA (2015) Public Data Archiving in Ecology and Evolution: How Well Are We Doing? PLoS Biol 13(11): e1002295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002295

I co-teach an MSc course in which the students are challenged to write a review paper on some topic in evolutionary biology. We (ambitiously) point them towards Trends in Ecology and Evolution as the kind of thing they should be aiming for. The best part of this for me is discussing topics with students. This often takes me to new places in the literature, makes me think hard about unfamiliar topics, and sometimes gives me opportunities to play with new data. This happened today, when a student expressed interest in understanding the links between body size and longevity in dogs.

Some background. Across most animals (vertebrates at least, I’m not so sure about the others), bigger animals live longer. Think elephants vs. mice. It seems kinda obvious. But the curious thing is that among breeds of dog, smaller animals live longer. I do a lot of comparative biology, and it’s always interesting to find trends that go in completely opposite directions. The challenge is then to answer three types of question: the proximate question (what current mechanisms, e.g. in development or physiology, cause these patterns?); the ultimate question (why did it end up this way over evolutionary time?); and the lineage explanation (can we propose a plausible set of steps that get us from a single ancestral mammal to the patterns we have today). Those are fun and enormously challenging things for the students to grapple with. But as a supervisor, I want to educate myself on the patterns themselves. I have my own questions. Are the patterns real? Are they convincing enough to care about? Do we have data to show it? Can we use the data to inform our answers to the important questions?

Playing with data is really fun. People are increasingly making their data available, and I hoped I’d be able to find suitable datasets to examine the student’s question, or at least demonstrate that the two conflicting trends are convincing enough that we should spend a long time thinking about explanations. For the between species data I turned to this paper [1, link fixed thanks to Ethan White], which describes a beautifully put together dataset on amniote life history traits, and which I happen to know about from hanging out on Twitter. Less than a minute after downloading the data, and with exactly 5 lines of R code, I can see for myself that bigger animals really do live longer, and that this holds true in birds, mammals, and reptiles. This is exciting! I’m not breaking any new ground here (there are umpteen papers on this and related patterns), but it’s fantastic to see the patterns for yourself, and explore them in whatever way you like almost as quickly as you can think of the questions.

I thought getting data on dog breeds would be more challenging, and to a certain extent it was. But I was lucky with my google-fu, and quickly found this paper [2], which contains a nicely-formatted table on longevity in 165 dog breeds. It took me about 5 minutes to cut and paste it into a google spreadsheet, clean up the formatting for what I wanted, and write the 4 lines of R code necessary to see the pattern in dogs:

The data here aren’t quite as convenient - dog weight is given in categories rather than point estimates. But it’s good enough to convince me that something interesting is going on here: unlike the between-species patterns, bigger dogs live shorter lives than smaller dogs. That’s kinda odd. And now I’m left wondering why, and what other data I can find that might help inform our thinking here. Is the same true of other domesticated mammals like sheep, horses, cows, etc.? Is it true of subspecies or isolated populations of wild mammals? What about humans?

Science is often difficult, slow, and tedious. But sometimes it’s easy, fast, and just great fun. Exploring data like this is one of my favourite things to do, and one of the biggest revolutions going on in science at the moment is the huge increase in the number of well-formatted and well-curated datasets that are made public for all to see and use as they wish. We’ve still got a long way to go on that front (shameless plug) [3], but things are moving fast, and it’s a great time to be doing science.

My commute home will be filled with papers on the causes and correlates of longevity in mammals. That will be rich brain-fodder for the weekend. I wonder what my 3 year old will think.

[1] Nathan P. Myhrvold, Elita Baldridge, Benjamin Chan, Dhileep Sivam, Daniel L. Freeman, and S. K. Morgan Ernest. 2015. An amniote life-history database to perform comparative analyses with birds, mammals, and reptiles. Ecology 96:3109.

[2] Adams, V. J., Evans, K. M., Sampson, J. and Wood, J. L. N. (2010), Methods and mortality results of a health survey of purebred dogs in the UK. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 51: 512–524.

[3] Roche DG, Kruuk LEB, Lanfear R, Binning SA (2015) Public Data Archiving in Ecology and Evolution: How Well Are We Doing? PLoS Biol 13(11): e1002295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002295